In Europe’s rapidly evolving food packaging landscape, fluorine compliance has become a critical factor defining product safety and market eligibility. Especially for fresh meat, seafood, and produce trays used in supermarkets, regulatory attention to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) has intensified. These substances, once valued for their oil and moisture resistance, are now under global scrutiny for their persistence and potential health risks.

- Why Fluorine and PFAS Matter in Food Packaging

PFAS are synthetic fluorinated compounds used to make packaging grease-resistant — a key property in meat trays, paper bowls, and molded fiber containers.

However, their chemical stability means they hardly degrade, leading to long-term environmental accumulation and potential human exposure.

According to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA, 2020), dietary exposure to PFAS already reaches levels of health concern. EFSA established a Tolerable Weekly Intake (TWI) of 4.4 nanograms per kilogram body weight for the sum of four PFAS (PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, PFHxS), reflecting the need to control migration even from packaging materials.

These chemicals can migrate into food, especially fat-rich products such as raw meat, during storage. Continuous exposure may affect liver function, immune response, and developmental health, making compliance a top priority for packaging producers.

- EU Regulations on Fluorine and PFAS in Food Contact Materials

Europe has one of the strictest frameworks for food contact material (FCM) safety worldwide.

Key regulations include:

- Commission Regulation (EU) No. 10/2011: Governs plastic food-contact materials. All fluorinated substances must be listed in the EU positive list and subject to overall and specific migration limits (SMLs).

- REACH PFAS Restriction Proposal (ECHA, 2023): Aims to restrict over 10,000 PFAS substances within the next few years, effectively phasing out fluorine-based coatings in food packaging.

- National bans: Countries such as Denmark (since 2020) have prohibited PFAS in paper and cardboard food packaging, setting a precedent for broader EU adoption.

These frameworks signal a unified European goal — zero fluorine in contact with food unless proven safe and essential.

- Scientific Evidence on PFAS Migration

Recent analytical studies show that fluorinated coatings are a major source of PFAS in food packaging:

- Schaider et al. (2017, Environmental Science & Technology Letters) found that 56% of tested fast-food and fiber packaging contained detectable fluorinated compounds, confirming widespread use and migration risk.

- RIVM (Netherlands, 2022) recommended Total Fluorine (TF) and Extractable Organic Fluorine (EOF) tests as fast-screening methods to detect PFAS presence in packaging before detailed LC-MS/MS analysis.

- Migration tests show higher PFAS transfer under fatty simulant conditions and extended storage times, a critical concern for fresh meat trays stored under refrigeration.

These findings emphasize that compliance cannot rely on supplier declarations alone — quantitative testing is essential.

- Market Transition: PFAS-Free Alternatives

The OECD (2020) and CHEM Trust (2024) have documented rapid innovation in non-fluorinated barrier technologies, including:

- Bio-based coatings (starch, chitosan, PLA-based films)

- Polyethylene-lined trays for grease resistance

- Advanced hydrophobic treatments without fluorinated compounds

A 2024 survey by CHEM Trust found that over 60% of major European retailers are implementing “PFAS-free” policies across their private-label food packaging by 2026.

This trend clearly signals that PFAS-free compliance will soon become a prerequisite for market access.

- Ensuring Fluorine Compliance: Best Practices for Manufacturers

Manufacturers and exporters to the EU should establish a robust compliance process that includes:

- Raw Material Control

Conduct Total Fluorine (TF) screening using Particle-Induced Gamma-ray Emission (PIGE) or Combustion Ion Chromatography (CIC). - Migration Testing

Use fatty food simulants per EU 10/2011 Annex V, simulating worst-case storage conditions. - PFAS-Specific Analysis

Confirm negative TF samples through LC-MS/MS for regulated PFAS compounds. - Documentation and Declarations of Compliance (DoC)

Provide traceable laboratory reports and compliance statements to buyers. - Adopt PFAS-Free Technology

Replace fluorinated coatings with certified non-fluorinated barriers and highlight this transition in product data sheets.

- Case Study: Leadgoalcn Packaging’s Fluorine-Free Innovation

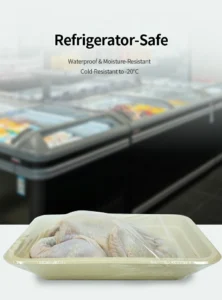

At Leadgoalcn Packaging, we specialize in eco-friendly, PFAS-free fresh food trays for meat, seafood, and produce applications.

Our R&D team has developed fluorine-free hydrophobic coatings that maintain excellent oil and moisture resistance without compromising recyclability or food safety.

Every production batch undergoes:

- Total Fluorine Testing (<20 ppm) based on RIVM methodology

- Migration testing under EU 10/2011 protocols

- Independent third-party verification for PFAS-free claims

This ensures European supermarket compliance, reduced liability risks, and improved brand trust for our partners.+

- Conclusion

Fluorine compliance is more than a regulatory requirement — it’s a competitive advantage.

With EU regulators tightening restrictions and consumer awareness rising, the demand for PFAS-free, certified-safe trays will continue to surge.

Manufacturers that embrace early testing, transparent documentation, and fluorine-free technology will lead the next era of sustainable and compliant food packaging in Europe.

References

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority). (2020). Risk to human health related to the presence of perfluoroalkyl substances in food. EFSA Journal, 18(9):6223.

- European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). (2023). Annex XV Restriction Report: Proposal for a Restriction on Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs).

- RIVM (National Institute for Public Health and the Environment). (2022). Analytical methods for measuring total fluorine and extractable organic fluorine in food contact materials.

- Schaider, L. A., et al. (2017). Fluorinated Compounds in U.S. Fast Food Packaging. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 4(3), 105–111.

- OECD. (2020). PFASs and Alternatives in Food Packaging (Paper and Paperboard): Report on Commercial Availability and Use.

- CHEM Trust. (2024). Retailer Progress on Eliminating PFAS in Food Packaging: A European Market Survey.

- European Commission. (2011). Commission Regulation (EU) No. 10/2011 on plastic materials and articles intended to come into contact with food. Official Journal of the European Union.